Six Months for Healthy Watersheds

Investing in watersheds is a triple win that creates jobs and boosts local economies, benefits ecosystems and protects drinking water, and strengthens relationships with First Nations and Indigenous partners. Early numbers from the Healthy Watersheds Initiative show that, in just six months, project teams have created nearly 500 jobs and begun restoration work on more than 200 sites across British Columbia.

This week, the Healthy Watersheds Initiative team released Our Water, Our Future, an interim report capturing early wins and insights from projects teams working to restore and protect BC’s streams, rivers, lakes, and wetlands.

Just six months into the HWI timeline, we’re seeing strong progress on job creation, climate action, UNDRIP implementation, and watershed restoration.

Our Water, Our Future draws on data submitted through 51 project reports, 61 project work plans and budgets, and correspondence with project teams.

Jobs and Training

Early reports show that at least 467 jobs have been created or supported, with at least 230 more jobs expected to be created in the coming months. Notably, a significant share of these jobs have been filled by people who identify as Indigenous (135), adults aged 30 or younger (174), and/or women (240) – demographic groups that have been impacted the most by COVID-19.

We know that these figures are an undercount, as some projects have not yet reported on employment numbers. (During the HWI intake process, project leads estimated that more than 900 jobs would be created or supported.) Many project teams are still hiring and report that finding workers can be a challenge in some part of the province.

Workers assemble bird boxes on wetlands near Campbell River, BC. Wei Wai Kum, Wei Wai Kai, and K’ómoks territory. (Photo: Discovery Coast Greenways Land Trust)

In addition to employment, HWI grants support skills development for workers. At least 200 hires have completed training in Indigenous and western techniques for fish and water sampling, water monitoring, data management, field safety, land management, and the use of traditional plants and medicines. Training also helps to build long-term capacity within the watershed sector.

“We talk about restoration often, but we don’t always have the resources to do the effectiveness monitoring needed to make this work more meaningful,” says Taylor Wale, Project Lead with the Gitksan Watershed Authorities, which is restoring salmon habitat in McCully Creek.

“Now accessing HWI, we have been able to hire and train up six Gitxsan people, which has been such a great opportunity for knowledge exchange and capacity building. Six new staff for our small organization is a big undertaking, and while we are building capacity, we’re also learning how to delegate better, and who we can lean on in the future so that this work can continue to expand.”

Watershed Restoration and Climate Action

Watershed restoration work is underway at more than 200 sites across the province. HWI project teams are working across disciplines and sectors to protect and conserve the freshwater ecosystems we all rely on.

These projects support a wide range of work that incudes rehabilitating former industrial sites to support salmon habitat, developing Indigenous guardian programs to care for ecosystems, and creating natural asset management databases and data hubs that support community decision-making on fresh water and land use.

All 61 projects contribute to climate change adaptation or mitigation, with activities related to habitat restoration ($8M), adaptation ($7M), and flooding ($2M) reported most often by project teams.

Water monitoring provides valuable data on water quality, water quantity that helps communities with land use planning, water decision-making, and climate adaptation. Tŝilhqot’in territory. (Photo: Tŝilhqot’in National Government)

For example, the Tŝilhqot’in National Government is designing and implementing a water quality and quantity monitoring program to fill information gaps and support Indigenous-led water and ecosystem management. To gather this data, TNG has created crews of fisheries technicians and rangers.

“This has been an effective combination,” says TNG Fisheries Manager Randy Billyboy. “The Fisheries Technicians have been leading the data collection, and the Rangers bring their expert knowledge of the landscape. Everyone is doing a great job learning the new equipment despite the steep learning curve.”

Indigenous Leadership and UNDRIP Implementation

The Healthy Watersheds Initiative was designed to advance the implementation of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which is BC’s commitment to upholding the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Out of the 51 projects that submitted interim reports to the HWI team in June, 46 proponents (90%) indicated that their projects include activities (like habitat restoration, site reclamation) that support the continued exercise of Indigenous hunting, fishing, gathering and land stewardship rights. By working with Indigenous partners to restore lands, waters, and habitats that have been damaged by industry, HWI projects are demonstrating reconciliation in action and a commitment to UNDRIP principles.

Importantly, 19 of 61 HWI projects (31%) are being managed by a First Nation or Indigenous-led organization. Nearly three quarters (73%) of project teams are confirming or strengthening existing relationships with a First Nation.

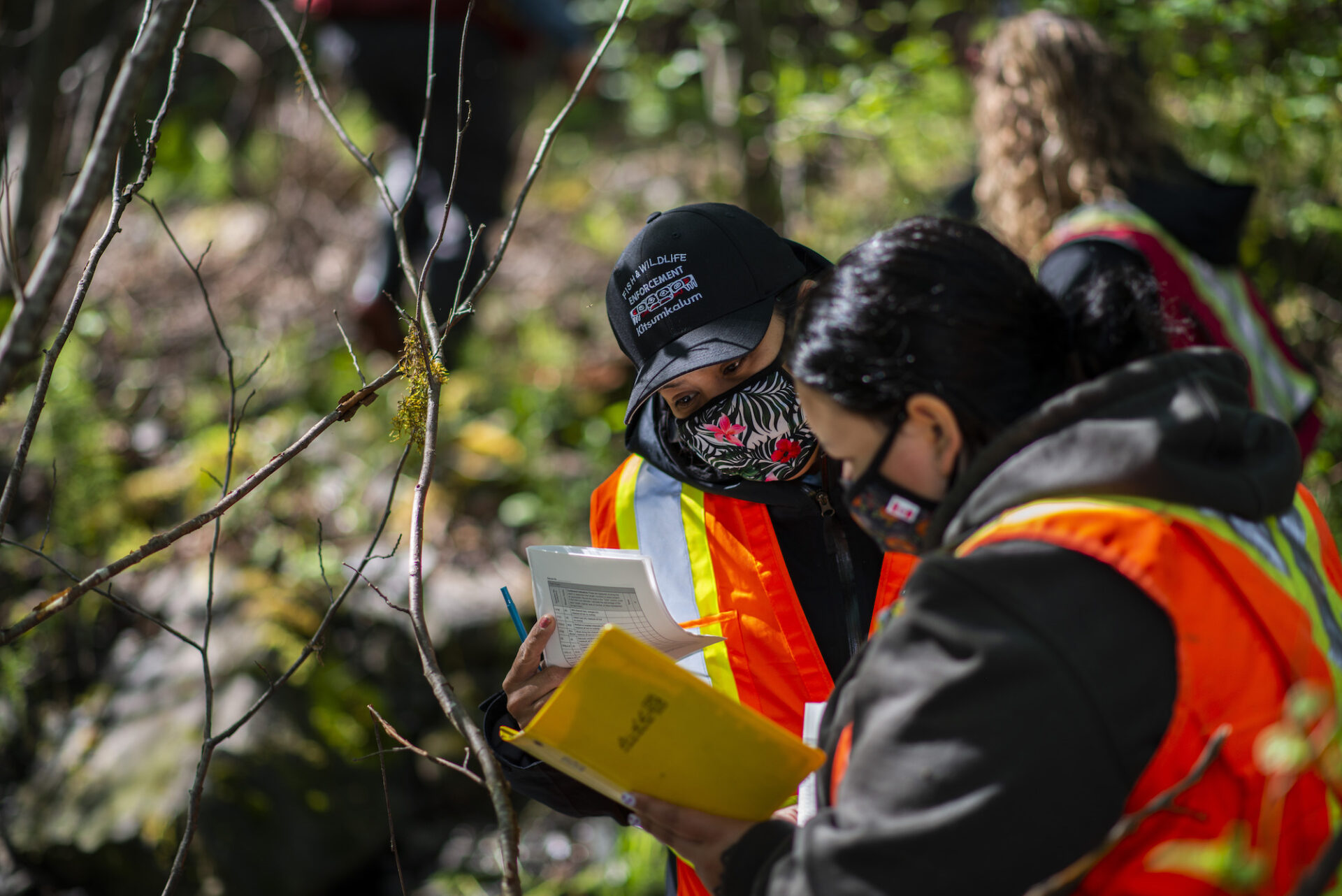

For example, SkeenaWild Conservation Trust is partnering with Kitsumkalum First Nation to restore salmon habitat near Terrace, BC.

“We are most proud of the fact that there are two Kitsumkalum youth working on this project,” says the project lead. “We are also very grateful for the connection we have made with Kitsumkalum and with Liitaalax Gibaaw (Sharon) in particular. It feels great to be genuinely welcomed to Kitsumkalum territory by the designated House representative in order to serve the wild salmon in restoring their habitat.”

Restoration work at Willow Creek. Kitsumkalum and Tsimshian territory. (Photo: SkeenaWild Conservation Trust)

What's Next?

This is an exciting time for the watershed sector. Within a few short months, HWI project teams are off to an impressive start: hiring workers, providing training, forging partnerships, carrying out projects, and building community capacity to care for freshwater ecosystems.

We’re beyond thrilled to see such an impact in such a short period of time – and you should be too! The Healthy Watersheds Initiative is an example of how governments and communities can work together for a future economy that’s just, sustainable, and climate ready.

In the coming months, project teams will continue work in their watersheds to restore habitat, improve access for salmon and other fish, gather data, adapt to climate change, and work with partners to plan for the future.

Projects are expected to finish by December 2021 and the HWI team is looking forward to sharing the final outcomes of these projects in a final report, coming in the spring of 2022.

Download the full report for more details on how this historic investment in watersheds is creating positive change for ecosystems, communities, and economies.

News release: "Healthier watersheds, wetlands for a stronger future" (31 August 2021, Government of BC)